On February 1, 1915, John H. Delaney, Commissioner of the New York Department of Efficiency and Economy (NYDEE), released a report roundly condemning the New York State Training School for Girls in Hudson. Financial extravagance, barbarous disciplinary practices, and an unfit superintendant were among the charges leveled against the Training School. The report also contained controversial recommendations to solve these problems. This report, which we shall refer to here as the “Delaney Report”, and reactions to it, will be the subject of a multi-part series on the Prison Public Memory blog. This overview is the first entry of this series.

The 933-page report was officially entitled, “Annual Report of the New York Department of Efficiency and Economy Concerning Investigations of Accounting, Administration and Construction of State Hospitals for the Insane, State Prisons and State Reformatory and Correctional Institutions.” It reported the results of a three-month investigation of the policies, practices, and prospects of 24 institutions, including 14 mental hospitals and 10 penal facilities.

Seven of the 10 prisons or reformatories were for the confinement and training of boys or men. Three of the facilities were designed for women or girls: the Prison for Women at Auburn, the New York State Reformatory for Women at Bedford Hills, and the Training School for Girls at Hudson.

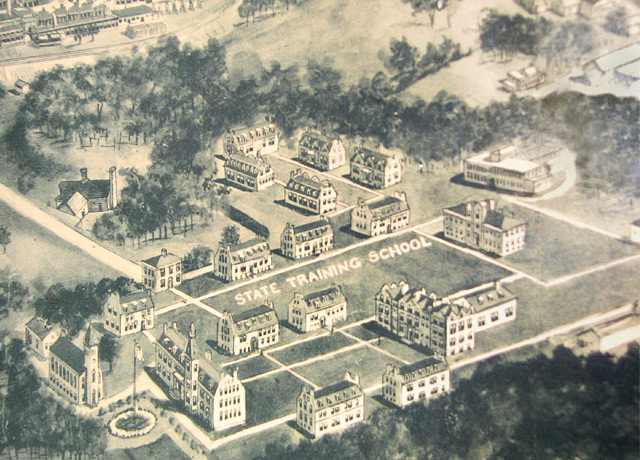

The Delaney Report opens with 14 pages of 23 photographs that appear elegant and stately in comparison to the mental health and prison facilities we are familiar with today. But the purpose of these photographs, which were taken by NYDEE staff members, was not to display exemplary architecture or design, but rather to highlight certain of the report’s criticisms of these institutions: dangerous, expensive, extravagant, inefficient, poorly designed, overcrowded, unsafe, unsuitable, and wasteful.

NYDEE was established in May 1913, but staff was not in place until January 1914 because of delays in the implementation of civil service exams and eligibility lists.

Though State hospitals for the insane were clearly the central focus of this NYDEE investigation, NYDEE expanded its attention to “an exhaustive investigation” of the prisons, reformatories and correctional institutions. Commissioner Delaney concluded that “the system of dealing with offenders against the laws of the State is wrong in principle and ineffective in operation, if such a haphazard method can be designated a system at all.”

“There is a routine of everyday life in the prisons, but no systematic plan of operation. In some prisons dungeon cells and bad food brutalize the inmates, while in others the effort of sentimentalists have produced a condition where men who have committed serious crimes against society are treated with the most distinguished consideration. Large associations of sympathetic men and women are continuously agitating in favor of more privileges for the criminal population. The natural and logical outcome of their efforts would be to make crime attractive as a means of securing an idle and comfortable living at the expense of the State. One prison in this State appears to be a prison only in the sense that the occupants must sleep and eat there.”

Commissioner Delaney felt that “work” was the cure for these ills of incarceration. “Every convict should earn his living while in prison,” the Commissioner opined. “Sanitary cells, good food and a reasonable amount of recreation should be furnished, but the sentence of ‘imprisonment at hard labor’ should be strictly enforced. The prisons of this State should be self-sustaining through their industries, and no punishment is too severe for lazy and rebellious convicts.”

On reformatories for young offenders, however, the Commissioner believed they should be “educational in the broadest sense.” In the wake of this review, he felt that reformatories, including the Training School for Girls in Hudson, were in need of “immediate reorganization.”

NYDEE examiners spent three days at the New York Training School for Girls in Hudson “for the purpose of ascertaining the necessity for the appropriations requested for the coming year by the Board of Managers, and to learn the actual daily routine of inmate life.”

Chief examiner Jackson and his “squad of accountants” start off their 17-page assessment with criticism of the facility’s school building, which they find “far beyond the requirements of the present school.” As in assessments of other facilities, Jackson and his staff examine the physical structure of buildings, the suitability of particular buildings for specific purposes, the daily lives of girls living in these buildings, the quality and dietary value of the food fed these girls, and the nature and quality of various educational, industrial, and disciplinary training.

Jackson and his staff make four major recommendations:

- The Hudson Training School for Girls is “most extravagantly conducted,” with the highest per capita cost at any institution in the State;

- Buildings in Hudson are described as wasteful in that “utmost extravagance prevails,” in opposition to any efforts to use existing buildings to their fullest capacity or to rearrange existing facilities for specific purposes as they arise;

- Discipline based on “absolute silence” is barbarous, severe, and unwholesome; officer attitudes toward girls in custody “defeat the purposes for which the institution was created,” and the institution’s “system of punishments” should be changed; and

- The current Superintendent is not capable of running the institution as a school, and not as a prison, and should be replaced.

Chief examiner Jackson’s report on Hudson concludes that girls at the facility require comradeship, outdoor play, education, and “technical training for practical purposes.”

“To accomplish the reformation of wayward girls, to give destitute girls or girls having had improper guardianship right ideas concerning life and its duties, a broad-minded, sympathetic and gentle woman is required, one who can teach high ideals by persuasion and not by punishment.”