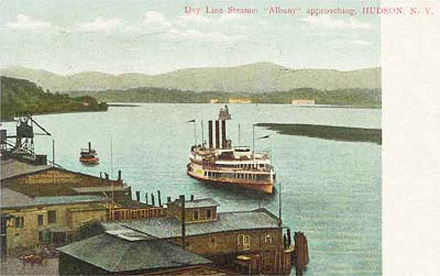

When Dr. M. E. Ross’s yacht pulled into the Hudson, NY harbor in July of 1936, few likely realized that it carried something other than an affluent figure on a Summer cruise. In fact, a new and formidable fight for racial justice had arrived in the form of Dr. Ross, a black physician from Harlem, who helped put Hudson on the agenda for civil rights reform.

One envisions race struggle arriving by other means, by foot, train, or practical car, perhaps, and surely there was some surprise when Dr. Ross stepped off as owner (not steward) of his yacht. But these were new and heady days, where the black middle class was growing, and an emerging civil rights movement was drawing on these and other advances.

Dr. Ross’ arrival marks a landmark expression of the growing political and economic force and national scope of the “black child saving movement,” a century long effort to advance racial equality in American juvenile justice, which began in the U.S. South in the late 1890s, and was at this very moment (the 1930s, in Hudson and elsewhere) being absorbed by the burgeoning civil rights movement.

Dr. Ross was on vacation, cruising in his personal yacht between New York City and Lake Champlain, along the historic Hudson River. The City of Hudson was not an expected stop, but when his wife informed him of a recent radio show discussing “Negro girls mistreated and segregated at the Hudson Reform School for Girls,” he decided to stop there. “Because I am a social-minded citizen and a taxpayer,” he explained in one of his complaint letters afterward, “I thought I would stop and make a personal investigation.”

He reports finding:

- “A beautiful green campus with about six (6) cottages, two of which were ‘Jim Crow’ for the use of Negro citizens of the State of New York…under the training of ordinary white individuals;

- “Negro girls are given training in washing and ironing, and even wash and iron the clothing of white inmates. (No wonder I mistook one of the white inmates for an official; she was so immaculately arrayed in clean clothes);

- “The white girls are given training in rug making. I saw no evidence of the same in ‘Jim Crow’ cottages;

- “The white girls have a well-equipped, modern, electrical hairdressing parlor where they are given training in beauty culture. In the colored cottage, I saw a basement room that was supposed to be equipped for the colored girls, but the only things I saw were one or two chairs in a dark, dingy basement.”

“This is the sort of thing we find when and where segregation exists – the white get the wheat, and the Negro the chaff,” he wrote, explaining that this not only wasted (his) tax dollars, but harmed the Harlem and Brooklyn neighborhoods most of these black girls came from and returned to, no better and likely worse-off for their time in Hudson. “The only place that I could paint a better picture,” he adds for good measure, “would be in the state of Alabama, or Georgia.”

Dr. Ross sent his complaints to Governor Herbert Lehman and Public Welfare Commissioner David Adie, also promising to “take this matter up with every social organization of which I know in the great city of Harlem.” When Dr. Ross’ yacht left Hudson, some must have been relieved to see him go, probably not realizing that his dissatisfaction and demands for change would return with greater force.

Dr. Ross sent his complaints to Governor Herbert Lehman and Public Welfare Commissioner David Adie, also promising to “take this matter up with every social organization of which I know in the great city of Harlem.” When Dr. Ross’ yacht left Hudson, some must have been relieved to see him go, probably not realizing that his dissatisfaction and demands for change would return with greater force.

Indignation was not enough to bring action. Rather, it was the growing strength of the NAACP, up and down the Hudson River, driving this monumental response. Of course, the momentous achievements were gradual, involving continuous agitation over months, years, and decades, and resulting in one of the earliest major legislative gains of the modern civil rights movement: a 1942 “Race Discrimination Amendment” formally barring racial or religious discrimination in tax payer supported child-welfare services.

Almost immediately after Dr. Ross’ letters of complaint, and surely inspired by others (e.g., the radio show mentioned), the state established a “Hudson Committee” to investigate the New York State Training School for Girls. By September of that same year (1936) the investigation was complete and the Board of Social Welfare supplied a letter outlining findings and recommending desegregation of housing, vocational training, and other aspects of the institution, so far as was practical. They also note staff reports of a “sex problem” among committed girls – most alarming when across race lines – contributing to their segregation rationale, and likely complicating desegregation. Indeed, desegregation was long delayed.

Dissatisfied with this report and plan, especially for its absolving the superintendent of responsibility in this matter, a key NAACP official replied later that fall with a letter to Commissioner of Public Welfare, accusing him and his Hudson Committee of “as perfect an example of punch-pulling and of whitewashing as ever seen.” He and the NAACP would take matters into their own hands, aiming to force desegregation at greater deliberate speed.

The NAACP had compiled similar reports from around the State of New York and nation for many years, so the Hudson case actually tied into a larger set of concerns about Jim Crow juvenile justice, in New York and across the nation.

This flyer, advertising a meeting of the NAACP in 1959, illustrates

concern about youth crime and justice throughout the state. The NAACP

was engaged with juvenile justice from its founding in 1910.

A native of Poughkeepsie, NY , Judge Jane Bolin was the first black

woman judge in the U.S. She served on the Manhattan juvenile court for

forty years (1939-1979), constantly pushing for the fulfillment of

democratic ideals.

New York State and the City of New York even more so had grown ripe for substantive change in the wake of the Harlem Riot and other factors encouraging accommodation of demands for liberal reform. In 1942, Judge Jane Bolin, the first black women lawyer to graduate from Yale Law and the first black woman judge in the U.S., and then NAACP president Walter White testified before the New York City Council and Board of Estimate in support of the NAACPs “Race Discrimination Amendment,” proposing to prohibit public funding of any charitable institution discriminating on the basis of race.

As a juvenile court judge and NAACP board member, Bolin was well aware of inequality in youth justice, up and down the Hudson, and she joined NAACP and court colleagues in taking bold and somewhat effective action to challenge these separate and unequal conditions. Informed by Judge Bolin’s insider perspective, White protested that “some nineteen child-care institutions in New York City receive a total of one million dollars in city subsidies…but exclude inmates because of color.” They insisted these institutions “[either] cease discriminating or get along without city funds [as] the City of New York cannot afford longer to be party to such discrimination.” Although the amendment was formally adopted months later it was not always enforced, and Bolin continued her protest of discrimination in case processing and segregated court services well into the 1960s.

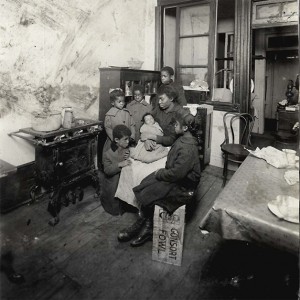

Religious organizations refused to open their organizations to black children even as New York City’s black population doubled between 1920 and 1930. The children in this family, pictured c. 1930, were eligible for fewer social services than their white peers. Collection of the Community Service Society, Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Legal gains around child services in New York, set in motion in part by agitators who sailed into Hudson in the Summer of 1936, helped outline desegregation strategies in other domains. The “Race Discrimination Act” Judge Bolin helped develop and pass provided a template for broader civil rights interventions, especially in public and private housing. The original appeal was revised to form the Brown-Isaacs Bill, focusing on racial and religious discrimination in public housing. Bolin also lobbied strongly on behalf of that bill, stressing the contradiction between this practice of discrimination and America’s “democratic professions,” and testifying to the impact of housing discrimination evident in her court, asserting that “it is perhaps little wonder that there should be finally rebellion against law and authority,” given their experiences of discrimination under law. The Brown-Isaacs Bill passed in 1951, followed closely by a bill focused on private housing.

Never the reluctant or disengaged citizen, Judge Bolin continued to press for racially democratic reform, writing to President John F. Kennedy a few years later as he considered an executive order barring discrimination in all federally-funded housing. As she had often shared with local and state leaders, she explained to the President how the domestic relations court provided “daily occasion to observe the physical, moral and psychological destructiveness on children and families of poor housing, racially segregated housing and racial discrimination in any form.” She urged Kennedy to outlaw any use of public monies “for the immoral, invidious and unjust purpose of injuring part of our citizenry.”

This extended episode of civic engagement warrants remembering for its significance in black and American history, including the local racial history of Hudson, and ultimately its contribution – like much of black history – to the greater realization of American democratic ideals.

Further reading:

Ward, Geoff. The Black Child Savers: Racial Democracy & Juvenile Justice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Smith, Eve. “Willingness and Resistance to Change: The Case of the Race Discrimination Amendment of 1942.” Social Service Review, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Mar., 1995), pp. 31-56