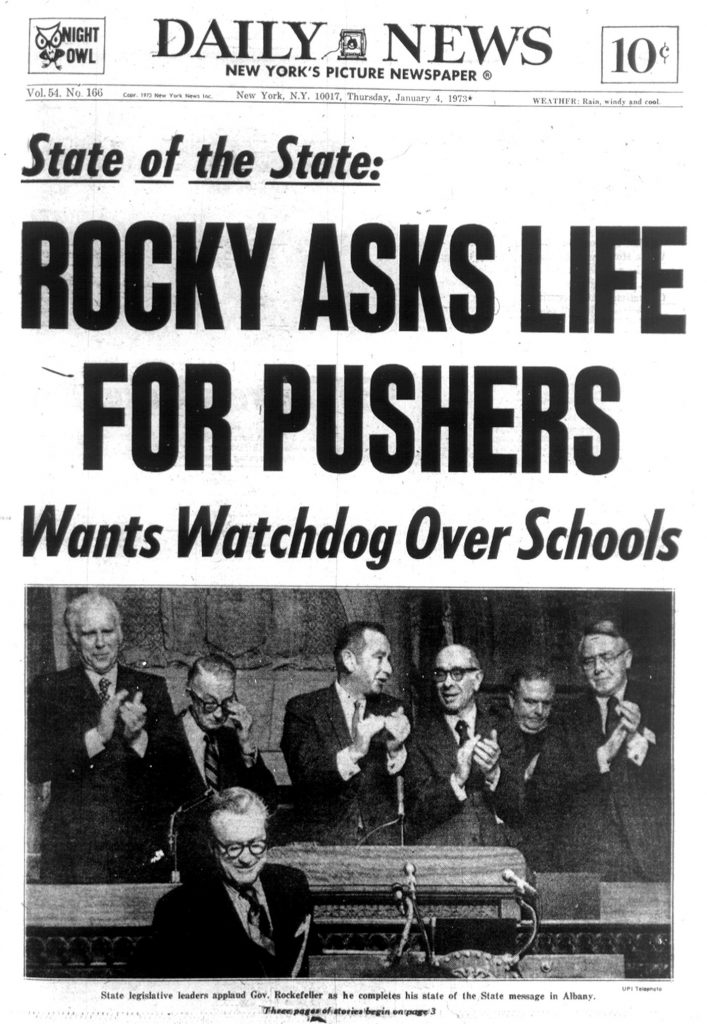

The Jan. 4, 1973, edition of the New York Daily News reports that Gov. Rockefeller’s State of the State speech called for a life sentence for drug pushers.

Bayview, a former rehabilitation center and jail that served various populations, has a history tied to drug legislation and policies at the Federal and local level. It provides a window into the impact of the Rockefeller Drug Laws enacted in New York in 1973. At the time the laws were passed, New York State defined drug-users as the central problem concerning drug offenses, rather than looking at the issue in other ways. The shifting emphasis from addiction—a way of looking at drug use as a medical and social issue—to criminality contributed to the enormous rise in imprisoned people over the last forty to fifty years. This brief history of the drug laws demonstrates the failures of that approach. Bayview was part of each chapter in the unfortunate story.

Since the first piece of significant legislation dealing with narcotics in the US, the Harrison Act of 1914, penalties implemented by drug laws have been known to aggravate drug-related issues rather than subdue them. Reason being: legislation passed with the intention of deterring drug use is created under the assumption that the threat of punishment will lead to conformity to the law. A footnote from Robinson v. California (1960) decision points out a flaw in this assumption:

“It is the very severity of law enforcement [which] tends to increase the price of drugs in the illicit market and the profits to be made therefrom. The lure of profits and the risk of traffic simply challenge the ingenuity of the underworld to find new channels of distribution.”

This trend also appeared during the Prohibition, where the underground economy created by banning a popular substance soon caused more problems than it solved. So, despite the steady increase of drug-related legislation passed between the 1910s and the 1960s, especially in the cities, the country’s drug problem had become overwhelmingly vast. Then, in 1965, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) agents were granted permission to carry firearms and powers of search, seizure, and arrest. Between 1966 and 1969 federal drug arrests increased from 22,000 to 67,000. In New York, the problem of mass incarceration was exacerbated following a shift in focus from drug rehabilitation to drug criminality.

Propelling that shift forward were the failures of New York’s ill-equipped drug agencies. In 1967, in what has been interpreted as a political move to provide treatment facilities for addicts, Governor Nelson Rockefeller created the Narcotic Addiction and Control Commission (NACC)—who would use Bayview as one of its facilities. Although the NACC eagerly promoted itself and published information on seeking entry into its treatment program, it was never explicit on how the treatment they provided would lead to rehabilitation and release. The NACC underwent serious scrutiny for its failure to rehabilitate their “clients” and for having no impact on reducing street crime. Even Rockefeller admitted, “We have achieved very little permanent rehabilitation, and have found no cure.” Declared too costly and ineffective, the NACC was disbanded 1973.

Increasing severity of punishment for those found with narcotics did little or nothing to deter drug use and sales. Preceding the introduction of federal and state drug offence deterrence measures in the 1910s, “criminal addicts” were unheard of; addiction was a health-related issue. Regardless, in 1973, already having funneled $1 billion into the “war on drugs,” Gov. Rockefeller introduced the unprecedentedly harsh Rockefeller Drug Laws stating, “I have one goal and that is to stop the pushing of drugs and to protect the innocent victim.” The laws, which politicians and drug treatment experts have deemed “draconian” since they were initially presented, called for mandatory prison sentences of 15 years to life for drug dealers and addicts—including those found with small quantities of marijuana, cocaine or heroin.

These policy changes led to the first of Bayview’s transformations. Prior to the drug laws’ passing, as a result of the NACC’s initiatives, The YMCA Seamen’s House in Chelsea was purchased by the government for $3.9 million and renamed the Bayview Rehabilitation Center in 1967. When the commission was disbanded and the Rockefeller Drug Laws were enacted, formerly committed addicts across the state were met with long prison sentences. Concurrently, the NYS Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS) was struggling with the results of a prolonged climb of incarceration numbers and in need of beds—a problem that worsened with the sharp increase in prison sentences due in part to the Rockefeller Drug Laws. Like the correctional system, Bayview had facilities of varying security levels for its “clients”. So, when the DOCCS began to take over the failed drug agencies’ facilities, Bayview easily converted from a rehabilitation center to a men’s correctional facility in 1974.

Soon after, in 1978, Bayview would become a notorious women’s prison.

Works Cited:

“A Vertical Institution: Bayview” DOCS TODAY, Nov 2001, accessed Apr 29, 2016. http://www.geocities.ws/MotorCity/Downs/3548/facility/bayview.html

Griset, Pamela. “Can’t New York Learn From Rockefeller Drug Policy Failures?” The New York Times. March 8, 1995.

Trilling, Carol. “Rockefeller’s Drug Law: Playing Politics with Addiction”. The Nation. November 9, 1974.