Fannie French Morse became Superintendent of the New York State Training School for Girls in 1923 and shortly thereafter she began stirring things up. Morse was an advocate of reform, which in the 1920s meant improving the lives of girls. As she noted a year later, “in the institution every effort should be made to make [the eelinquent girl] feel herself a part of her own remaking”.

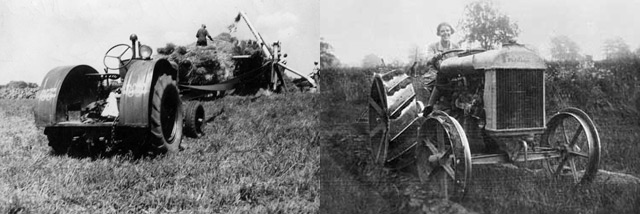

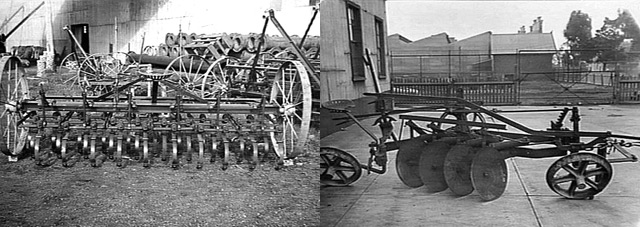

Sometime in 1924 Morse wrote a paper, which later appeared in that year’s annual report, expressing her belief that girls should be able to farm at the school. Training school boys do it, she said. Why not girls?

“The incorrigible, the emotional, the neurotic, the girl confused with the very tangle of circumstance – in the stabilizing and restoring influences of the farm life many a one can find balance and relief. To the restless girl, calling for another interest, another experience, another adventure before the last is scarce complete, the numberless and shifting interests and movements of the farm life furnish an almost exhaustless source.”

Morse’s four-page case for farming included economic, gendered, nutritional, disciplinary, behavioral, environmental, and recreational reasons. Once girls became farmers, Superintendent Morse even reckoned, they could garner farmer husbands.

Morse noted that farming programs at juvenile institutions were a source of income for the state. A primary economic problem in implementing such a program, however, was the availability of labor, but she felt that confined girls, like incarcerated boys, provide an accessible, and perhaps more natural, workforce.

With this proposal, Superintendent Morse brought a gendered perspective, “The peace of girl joy labor born out of the beckoning out-of-doors knows no challenge and almost no limitation. It is the concerted opinion of those who have worked with both girls and boys that the girl brings to the growing plant life an art not known by the boy of like age – the art of fostering delight which perhaps is an expression of the awakening maternal. Then, given the kind and amount of labor which three or four hundred girls fairly effervescing with energy represent, the question of labor is well nigh eliminated.”

Beyond the economic advantages of farming, Morse argued that food itself was at the center of the institution’s overall order. “There is in an institution no greater disciplinary force for good,” she stated, “than good, nourishing food” — just the type of food that could be grown or raised at the girls’ school, with its acres of open, rural landscape.

“A big milk supply in an institution knows no by-product. In an institution it is the greatest of all food assets, from its first form to cream, butter, buttermilk and cheese — to say nothing of its possibilities in added nourishment in cooking.” Plus, she added, a local farm would produce more milk product than the state was likely to purchase.

For Morse , institutionally-purchased food paled in light of “the wholesome variety of the farm.” Freshly grown foods, she said, were healthier than canned goods. Also, she felt that farm-grown -and -raised food could reduce or eliminate the need for “purchased food.” As she observed, “The present-day perfected methods of canning and other forms of storage represent such conservation of supplies for the winter as well-nigh eliminates the purchase of canned goods.”

Morse, concerned about “the pauperization of the individual” at state institutions, set forth a series of arguments that farming counters idleness,improves physical fitness, develops new outlooks, allays restlessness, and even empowers. She saw “no greater menace” than idleness.

“Idleness or lack of interest is the great unmake of the inmate, and the great stir-up of trouble in the discipline of the institution. Deadly, soul-killings, body-crippling is the close shot-in-ness of the institution, void of natural adventure and thrill. Youth for its very intake well demands elemental and vivid moments. The spillover, or seeking for the exploitation of adventure and thrill has brought the average delinquent girl to the institution. Her rehabilitation must come, not through the elimination of these forces, but a substitute. It must come from the ramming out of the old with a new and bigger and more thrilling, a more vivid and more unique interest than the old. It must be for her a matter of arrested attention; a quick giving of a new slant; an almost cold-water plunge into the unusual interest that often appeals because of its uniqueness.”

Morse believed a “big” occupation-oriented perspective was necessary. “As part of this program,” she concluded, “nothing can play a greater and more moving part than a farm – a farm with its varied interests; a farm with its stretches of freedom; a farm with its animal and plant life; the wholesome out-of-doors; the closeness to the great interpretative elements of nature; the plant and animal life that so humanizes; the unique employment which so thrills.”

It would appear that Superintendent Morse was a persuasive advocate: Sometime in 1924, the New York State Training School for Girls received the approval and funding necessary to rent a farm six miles away and the rental was renewed for several years more…

Resource

Morse, Fannie French (1925). The Farm as a Factor in Training Delinquent Girls. In: Board of Managers. Twenty-First Annual Report of the Board of Managers of the New York State Training School for Girls at Hudson, N.Y., for the Year Ending June 30, 1924. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company. pp. 20-24.

This story was researched and written by criminal justice consultant Russ Immarigeon, a resident of Columbia County, NY and regular contributor to the Prison Public Memory Project.